The Parrot Society UK

Disease Control at Bird Shows

Bird shows potentially pose an ideal opportunity for the spread of infectious diseases, and many instances occur where recently purchased birds fall ill a few days after such a show, when in their new home.

The diagnosis of the root cause of such disease, and confirming a 'chain of responsibility' poses a difficult detective problem for the avian veterinarian. The sick bird may be unwell simply as the result of stress and change of environment. Different temperature, humidity, diet, or water quality may all make a delicate bird unwell, without any infectious cause. This would especially apply to smaller species or young birds. The control of this aspect is mostly common sense: one should question the seller of the bird about its previous housing and diet, and then obviously do not put a bird that has been kept in a warm house in a cage straight in to an outside aviary. It is also important to see that the new bird is fed on much the same diet initially to that which its digestive system is accustomed. So many times as avian vets we see cases of illness in birds brought on by simple omission of these apparently simple steps.

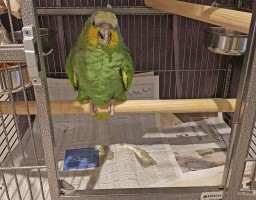

Ailing Orange-winged Amazon parrot - sitting hunched and fluffed-up, with watery droppings

One should remember that all these birds will have undergone some degree of stress, and some cope better than others. They will have been moved from their original home to the show venue, often travelling long distances in small boxes, then put on display in a noisy hall, adjacent to unfamiliar species, with bright lights, possibly draughts, historically often cigarette smoke, and a general total shock to the system. They then may be caught up and transported yet more hours in a car or truck to the new home, and dumped unceremoniously into a different cage or aviary, with strange companions and environment. Wouldn't you feel unwell after such treatment?! Such birds should be treated with care and respect, and at the very least should be offered quiet, subdued conditions in which to recover from their ordeal, with the addition of electrolyte fluids such as Spark, Polyaid, Critical Care Formula or the like as a 'pick-me-up' while they get over the shock.

If a bird does fall sick in these circumstances, usually within hours or a few days of the show, then it is obviously not the responsibility of the vendor. Equally, if the newly purchased bird is put straight in with existing stock, the home population may be carrying bacteria or viruses to which they have an immunity, but the new bird does not. These germs spread to the new bird; it becomes ill within a matter of days as a result of the infection, and immediately the purchaser is blaming the vendor for selling a sick bird!

Conversely, many a bird taken to a show is harbouring such germs with which it is in balance, but the added stress as outlined above will weaken the bird's defences and allow the infectious agents to multiply and cause disease. Worse, if the new bird is put in with existing stock, the reverse of the above scenario can occur, and the new owner's established birds become ill. Once again, the vendor can be blamed for selling a bird as a 'carrier' of infection.

In all the above situations, the vendor may be blamed, but in the first two cases there is obviously no liability, and in the third, the bird appeared perfectly well at the time of the show, so how was he/she to know the bird was carrying infection? The situation becomes even more complicated when the possible infections have a long incubation period, such as Psittacosis (Chlamydiosis), Psittacine Beak and Feather Disease, or Proventricular Dilatation Disease. In these cases, illness may not show for as long as nine months after exposure, so how can anyone possibly confirm the source of infection then?

The most serious potential problem occurs when an unscrupulous vendor knowingly takes a bird that is sick, or has been in contact with infected birds, to a show for sale (and yes, regrettably there are people out there who would do such a thing!)

Thus, the control of the spread of disease at bird shows rests in three areas. Firstly the vendors should ensure that they take only healthy stock to the show, and they should make every effort to ensure that the transport and carriage of the birds is done as efficiently and with as little stress as possible. Cages and boxes should be clean and not overcrowded; rest stops on a long journey should be taken, with an opportunity to check the birds and give food and water. Probiotics and/or electrolytes may be given in the few days before the show to boost the birds' immune systems. Sellers should be prepared to discuss with potential purchasers the housing, environment, and diet from which the bird had come. A written receipt with some form of agreed guarantee period should be given with the bird. No-one in fairness can guarantee a bird will not fall sick for nine months, but an acceptable period would be perhaps 4 - 7 days. Stalls or tables displaying the birds should be uncrowded and clean, with fresh food and water available to the birds. Any individuals showing signs of distress should be removed from display, and if necessary checked by the show vet.

Secondly, the show organisers have a responsibility, by outlining in advance the requirements for cage size and cleanliness, together with warnings about overcrowding and smoking. These requirements then need to be enforced on the day by inspections on admission, and regular checks by a team of stewards. A show vet should be appointed, and a room set aside for the quiet examination and isolation of birds. Any transgression of these requirements should be treated seriously: at least with a warning, followed by expulsion from the show for a persistent or serious problem; and perhaps a ban from attending future shows. Any birds appearing obviously distressed or sick should be taken to the isolation room for examination by the show vet. In some circumstances, the provision of disinfectant foot baths or mats at the show hall's entrances may be required.

Thirdly, the purchaser has a responsibility, to look at his/her potential purchase with a critical eye, and choose only the bird that looks alert, bright-eyed, and with tight, clean plumage. Do not ever choose a bird that looks subdued, fluffed-up, and hiding in the corner. Do not smoke while peering into the cage to make your selection. Ask the seller about age, sex, husbandry, diet, breeding history before you make your decision. Check out other tables and sellers in the show.

When you have made your choice, remember who sold the bird and where he/she was! Preferably a name and a table number. It is no good complaining to the show organisers three months later, that you bought a Norwegian Blue from "the chap just inside the third door on the right", and the bird has just died. Get a receipt and some form of guarantee from the seller.

Then take care of your purchase. Don't shove it in a small box with half a dozen other strange species, and then drive halfway through the night in a bumpy, draughty, smoke- and diesel fume-filled van to arrive at your destination in the early hours. Then you leave the bird(s) in the box overnight, or worse, turn them out into a strange aviary in the dark, with no clue as to where food, water, and perches are, and expect them not to be stressed! Give them food and water, preferably with electrolytes or probiotics in, and give them peace, warmth, and rest.

Keep them isolated from existing stock until you are happy that they have settled and recovered from the journey, and are showing no signs of illness. To guard against every possible infection that may occur, you would be quarantining new birds for over a year, which is obviously impractical. However, 10 - 14 days will allow most common infectious diseases to show themselves, and give the birds time to settle in their new home.

Report any signs of trouble immediately to the vendor. It is no good complaining three months later that "the bird was sick two days after I got it home, and then it died". You need to warn the vendor immediately of a potential problem, so that he/she may be aware of trouble, and check their remaining stock. If the bird unfortunately dies, then arrange a post-mortem examination. A conclusive result is unfortunately not always possible, but in most cases a diagnosis will be made that will pinpoint the cause of the bird's demise, and give some clue as to the origin of the problem.

In the end the saying "Caveat Emptor" (let the buyer beware) pertains particularly to the purchase of birds from shows. If you take the simple precautions outlined above, you should end up with a successful and healthy purchase, and if there is a problem it will be sorted out amicably with the organisers and the vendor. However, if you expect to buy cheap to get a bargain, or take short cuts in the care and management of your new charges, then you have only yourself to blame.

Alan K Jones BVetMed MRCVS

January 2020