Ultraviolet Light & Skin Cancer

The following article was published originally in the magazine of the Parrot Society Volume 52, January 2018.

To those of you who may be colour blind, or partially sighted I extend my sympathies, and my apologies for what is to follow, since you unfortunately miss out on so much already. To those of us who are blessed with ‘normal’ vision, try to imagine for a moment how life would be if we could not properly see those wonderful autumn colours, or the rainbow hues of the many parrot species that we look after, and enjoy so much. It is, after all, the glorious plumage of these birds that has attracted most of us to them initially.

Ever since the superb presentation by Mark Stafford at our 50th anniversary seminar at Chester Zoo in 2016, 50th Anniversary Seminar part 2I have more than ever been aware of the extreme sensory abilities of parrots. The pinnacle of these senses must surely be their eyesight. Apart from the superior processing function of eyes and brain that Dr Stafford described, there is their greatly enhanced colour vision compared to that of human beings. We know that parrots can see the ultraviolet wavelengths of light, as well as the red, green and blue section of the spectrum, which is all we mere humans can visualise. We also know that ultraviolet radiation is important for the synthesis in the skin of vitamin D3. To that end we realize that it is important to supply UV-spectrum lighting for parrots kept indoors, with no access to natural daylight. There is now a wide range of bulbs and tubes available for birds and reptiles, with various ways of mounting them, and in several wattages. Against that is the risk of skin cancers in susceptible humans, following excessive or prolonged exposure to ultraviolet radiations in sunbathing – be it in natural sunlight or in tanning salons.

Concern about this risk of skin cancer prompted a recent enquiry on a Facebook forum for the rescue and rehoming of parrots. The short answer is that there should be no concern about skin burns or skin cancer resulting from ultraviolet lamps intended for birds and reptiles, if used correctly, since they are not sufficiently powerful to burn our skin. They mimic early morning sunlight, rather than full intensity midday beams. Ultraviolet light can be roughly sub-divided into three sections. UVA wavelengths are those responsible for allowing birds to see their full potential range of 100 million colours with their tetrachromatic vision. Since ultraviolet light does not penetrate through glass, indoor birds will receive no benefit from the natural UV in sunlight, so their world will be forever dull, if not assisted. Living in this way has been compared to a human (with trichromatic vision of just 1 million colours) trying to exist in a photographic darkroom, with just the dull red safelight bulb available. Imagine how that would be! The ability of parrots to see the full range of this wide spectrum is important in identifying the ripeness or otherwise of foods, and the identification of individuals – especially of the opposite sex, or juvenile members of the family. Without the provision of an ultraviolet light source, indoor birds are forever condemned to severely limited vision.

We see a black Mynah bird with yellow wattles and beak (left), other birds see much more colour in the UV range (right)

UVB wavelengths are those involved in the synthesis of vitamin D3 in the skin. Species with a higher demand for this vitamin, or those naturally living below leaf canopies (African grey parrots, macaws) tend to have more bare skin available to make use of this effect. It has been postulated that some cases of feather plucking in captive indoor parrots may be an attempt by the bird to expose larger areas of skin to make better use of the limited light levels available to them.

UVC wavelengths are totally filtered out by our atmosphere, so are not found naturally on earth. They are generated for use in high-powered clinical cleaning and water purification units. Sunburn is caused by prolonged over-exposure to both UVA and UVB, both of which are found in quantity in intense natural sunlight and sunbed tubes. Prolonged over exposure to such radiation results in a genetic change in skin cells, predisposing to cancer formation.

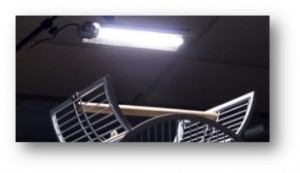

Commercially available ultraviolet lighting for birds and reptiles is effective over only a very short distance. Your birds will receive no benefit from such a lamp mounted on the ceiling: it would have to be between 8” (20 cm) and 15” (37.5 cm) away from the bird’s closest perching area, depending on the power of the lamp. In addition, the UVB component of the lamp’s output is no more than 2.4% of the total output. Such positioning will allow the parrot its full spectrum of colour vision, plus the ability to manufacture vitamin D3, while still allowing it to move away into ‘shade’, as it would naturally in the wild.

For a human to run any risk of burning from this low-powered output, one would have to sit within a foot (30 cm) of the light source for several hours! So I repeat that there is absolutely negligible risk of humans being either burned or developing skin cancer from the use of pet-quality ultraviolet lighting on their birds. There are provisos: people with ultra-sensitive skin, or taking certain medications will need to be more cautious. The use of tanning lamps or LED lights not intended for birds is not advised. While cleaning out cages or working close to these lamps, it is advisable to switch them off, especially if the procedure will take some time. Mounting of the lamps must preclude the bird having any access to the wiring. Your bird must have sufficient space to move away from the light source: being permanently as close as 6”-8” to the lamp can cause cataracts in the eyes.

I can best summarise with a quote from John Courteney-Smith of Arcadia lamps – “All in all the risk of human burn when the product is used correctly is tremendously low. The benefits to the birds, however, are tremendously great”. See also Arcadia bird.com

AKJ Feb 2018