How to Sex Captive Birds

Extracts from 1907 publication, How to Sex Cage Birds© - an interesting historical article!

by R.J.McMillan, UK.

"Introduction

Amongst technical ornithologists it has been a custom, much to be deplored, to describe all birds in which the sexes do not exibit marked differences in colour of plumage, or well-defined external ornamentation, as follows :- "Female similar to Male" but happily, in recent work done in the United States where the most careful measurements of every part of each individual of a species are being recorded, and where considerable trouble is taken to ascertain the sex of preserved skins, the more or less constant differences which presumably exist between the sexes of all birds are beginning to be made apparent.

Psittaci, or Parrots

The sexes of which are not always easy to recognise, though if the late Mr Abraham's distinction is constant, and he showed it to me in the sexed skulls of at least half a dozen widely different groups of Parrots, one ought always to be able to tell the sex by feeling the hinder angle of the lower jaw, which is more pointed, and developed farther backward in the female than the male, thus giving space for the attachment of a more powerful muscle, which will account for the fact that the bite even of a female Budgerigar will draw blood, whereas that of a male of the same species will not. In addition to this character, the females of many of the parrots are smaller than the males, and have rounder heads; in some, the iris is paler in the females, and it is probable, if careful measurements were taken, that most of them have shorter wings than their mates; in some the bare patches on the face differ sexually, and, as a matter of course, the form of the beak is always worth comparing, and the colour of the cere at the base of the upper mandible.

Adult hen Sulphur-crested Cockatoo showing distinctive red iris. Cock bird's would be dark brown or black (AKJ)

The Ka-Kas (Nestoridae).....According to Gould, these strange birds do not move about the earth with the awkward, shambling gait of the more typical Parrots, but by a series of leaps, exactly after the manner of the Crows.

Kea Parrot or Mountain Ka-Ka (Nestor notablilis)......I could find no sexed skins of this bird. I probably overlooked them, as a pair is noted in the catalogue. Count Salvadori says that the female has the tints of the plumage duller than the male, and the dusky marking of the feathers broader. Doubtless it differs also in form of beak, as in the succeeding species.

Common Ka-Ka (Nestor meridionalis)......The beak of the male is much larger, and with more curved terminal hook than that of the female.

The Lories (Loriidae).....The sexes of these birds differ very little in plumage, but there is always a more or less well-defined difference in the outline of the beak when viewed from above; as this difference is similar to that which occurs in many of the Finches, I have not thought it worth while to illustrate it.

Red-Fronted Lory (Chalcopsittacus scintillatus).....The beak of the male is considerably broader than that of the female, and has a longer terminal hook; the colouring of the top of the head is perceptibly brighter in th male, and this appears to be a constant character so far as I could judge by comparison of the sexed skins in the Museum.

Blue-Streaked Lory (Eos reticulata).....The beak of the male is distinctly shorter than that of the female, fuller towards the tip, and with a broader terminal hook; the colouring of its head is also unquestionably brighter.

Blue-tailed Lory (Eos histrio).....Oddly enough in this species the male beak is much narrower than that of the female, and has a noticeably shorter terminal hook.

Red Lory (Eos rubra).....The beak of the male is distincly broader at the base than in the female, and the scarlet colouring of the head is brighter.

Violet-necked Lory (Eos riciniata).....In the male the base of the beak is broader than in the female, and the culmen or ridge makes a more perfect arch.

The Three-coloured Lory (Lorius lory).....The skull of the male appears to broader than that of the female; the beak is noticeably broader, but appears to vary greatly with age, the largest birds having by far the broadest beaks.

Purple-capped Lory (Lorius domicella).....I could discover no sexed female; but doubtless the beak of the male is broader at base.

Green-tailed Lory (Lorius chlorocercus).....The male beak is broader at the base and rather fuller towards the tip than that of the female.

Blue-thighed Lory (Lorius tibialis).....I found only one skin in the Museum, but doubtless the sexes differ as in the allied species.

Chattering Lory (Lorius garrulus).....I found three sexed males but no sexed females, but it is probable that the beak of the male is broader at base than that of the female.

Yellow-backed Lory (Lorius flavo-palliatus).....The base of the beak is broader in the male, and the arch of the culmen greater. At the commencement of his account of the Lorikeets (Parrakeets, p. 3), Mr Seth-Smith observes: "The sexes are, so far as I am aware, alike in plumage in all of the Lories, but, in most cases at least, the females are slightly less in size than the males, and possess a smaller and more effeminate-looking head."

Blue-faced Lorikeet (Trchoglossus haematodes)

I could discover no skins in the Museum series sexed as males; but two sexed as females show remarkable differences in the outline of the beak, and although it is possible that they may be due to age, they are exactly what one would expect in opposite sexes. It is, I think, worthy of note that the brighter?coloured bird, in which, like the other unsexed specimens, the breast is strongly tinged with orange, shows a beak of the male type as they also do, whereas the other, which possesses a beak of the female type, shows hardly a trace of this colouring.

Lovebirds (Agapornis)

Red-Faced Lovebird (Agapornis pullaria)......The male is larger than the female, his beak is longer, less arched, with longer terminal hook. The female, also, has a broader beak, has green underwing-coverts (whereas the male has black); her beak is less bright in colour, and her face and rump paler.

Conures (Conurus)

Petz Conure (Conurus canicularis) .....The male has a broader and shorter beak than the male.

Ringnecks and Allies (Palaeornithinae)

Mauritian Ring-necked Parrakeet (Palaeornis eques) .....The female differs from the male in having no bluish tinge on the occiput, no rose collar, and no black mandibular stripes, there being only a trace of the latter of a dark green colour; bill entirely dusky black. Dimensions as in the male, but the bill a little smaller.

Alexandrine Parakeets - cock on the left, with dark neck ring, hen on right with no ring markings (AKJ)

Long-tailed Parakeet (Palaeornis longicauda)

In the males the beak is broader at base and more triangular when viewed from above than in the females; the terminal hook is also longer. In the female the entire beak is horny brown, and the mandibular stripes are dark green instead of black.

African Pioninae

Jardine's Parrot (Paeocephalus gulielmi).... The male is larger than the female, and has a considerably heavier and more powerful beak."

Extracted by R.J.McMillan

Alan K Jones BVetMed MRCVS, PSUK Chairman adds in 2018 - "A very interesting extract, with some out of date scientific names! Many of our parrot species are known as sexually monomorphic, meaning that male and female are indistinguishable - at least to human eyes. There are some that are obviously dimorphic, with Eclectus parrots being perhaps the best known, where cock birds are primarily green and hen birds are primarily red.

Pair of Eclectus parrots - red and blue hen on the left, green cock bird on the right (AKJ)

Other, more subtle, distinctions include the dark ring of feathers in adult male Psittacula parakeets, the difference in cere colour of budgerigars, and the red iris colour of adult female white cockatoos compared to the dark brown or black in adult male cockatoos. (See above) These are all well recognised by parrot enthusiasts, and those who spend more time observing their birds will notice even more subtle differences in head and beak shape between the sexes, especially where several birds can be visually compared at one time. This is particularly so with African grey parrots and many Amazon species, and is hinted at in the above article.

Now, of course, we have more sophisticated scientific methods of confirming the sex of parrots. Initially there was endoscopic (or 'surgical') sexing, using a small endoscope to look inside the bird to visualise its gonads (both testes and ovary are contained inside the body of parrots, with no visible external organs). This technique has the advantages of giving more complete information about the health and development of the gonads, as well as the internal organs, and will give an immediate answer; but the disadvantages are the minimum age (the gonads have to be large enough in a juvenile bird to be visible!), the need for a general anaesthetic, and the requirement for operator expertise and experience.

Endoscopic sexing of an anaesthetised Green-winged Macaw (AKJ)

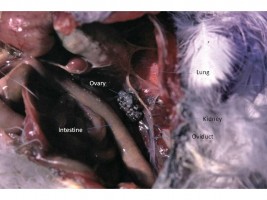

Annotated post-mortem pictures of gonads and associated organs. Left - ovary in a hen cockatoo. Right testes in a cock parakeet - unusually both with different pigmentation (AKJ)

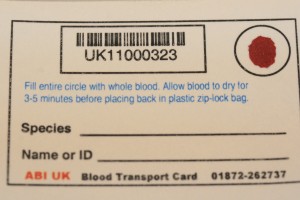

Now we have DNA techniques, whereby sex can be determined from a small drop of blood or fresh feather material, allowing simple, non-invasive, and early-age results. Disadvantages are a short delay in receiving the result, and the fact that the answer is a simple 'male/female', without additional health information.

Blood collected and spotted on to a collection card for processing at laboratory (AKJ)

In recent years it has become clear that birds are able to view light at the ultraviolet end of the spectrum, which will show feather colour much differently to the way humans see it. Soon it may well be possible to use this fact to sex parrots using a UV light source.

We will be pleased to receive further articles and information of interest to add to our Web Site or for publication in our Magazine.

Please forward by E-Mail to les.rance@theparrotsocietyuk.org or by post to:

Mr L A Rance

The Parrot Society UK.

Audley House, Northbridge Road

Berkhamsted,

Hertfordshire

HP4 1EH

Telephone 01442 872245

N.B. We review all submitted articles and the society reserve the right not to publish articles at their discretion. Their decision is final in all these matters and no further correspondence will be entered into.

Articles marked with the copyright symbol© beside the author`s name are copyright© the author. In these cases, copyright remains with the author/authors and the information cannot be reproduced without the additional permission of the said author/authors.