Re-thinking Food Presentation for Macaws

This article first published in our magazines for October/November 2019

By Charlotte James and James Brereton | University Centre Sparsholt

Introduction:

Wild parrots feed on a vast variety of foods. Specialist strategies include the nectarivorous habits of the rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus moluccanus) and lories (Lorius spp.). While many parrots are more generalist and may feed on a range of different food types, it is important to note that many species in the wild feed on fruit.

The Ara macaws are particularly well represented in both the private sector and in zoological collections, with thousands of individual birds being held in public zoos alone. As intelligent, attractive birds, it is hardly surprising that these animals are very popular with members of the public. In the wild, Ara macaws are highly capable problem solvers, and the blue and yellow macaw (Ara ararauna) as an example has been known to feed on foods as tough as coconuts (Cocos nucifera). In captive collections, fruit may be provided in addition to a seed or pellet-based diet for Ara macaws. Many collections provide the fruit component in a chopped format, so that the birds are better able to take hold of individual items. Keepers also suggest that carefully chopped items may be valuable for several other reasons:

- Less waste. The amount of food offered can be tailored more easily to a bird’s energy requirements if it is chopped, thus helping to prevent food being wasted.

- More diversity. Birds can be given a much greater diversity of food if they are given chopped, because multiple fruit types can be mixed into a medley.

- Easier to eat. The parrots can pick up each individual food item much more easily.

On the other hand, food items in the wild would not normally arrive in a ready-chopped format, and birds may sometimes not receive great diversity in their diets in the wild. Furthermore, macaws are well equipped to tackle complicated food items in the wild, with their well developed beaks, zygodactyl feet and mobile tongue. Armed with the ability to solve problems, the birds may actually benefit from challenges associated with difficult food items. Across the literature on zoo animal feeding, this debate has only been investigated in a handful of species, all of which are mammals. Previous research has shown that both macaques (Macaca silenus) and tapirs (Tapirus terrestris) actually eat more when whole food items are provided. Work with the coati (Nasua nasua) has also showed that aggression levels between animal actually decrease when large food pieces are given.

Blue and yellow macaw with whole banana. Note zygodactyl foot & fleshy tongue

To scientifically investigate the suitability of both the chopped and whole food formats for parrots, we developed a behavioural study which was undertaken at Beale Wildlife Park and Gardens, which is situated in Pangbourne, Reading. (See Beale Park) To trial the project, we selected a well established pair of blue and yellow macaws, who are housed in a mixed species exhibit with Jenday conures (Aratinga jandaya) and Patagonian conures (Cyanoliseus patagonus).

Our methods:

Our study subjects were a male and a female blue and gold macaw, housed in a large exhibit with an indoor perch. The standard diet for the pair was a mixed seed diet, provided ad libitum, alongside a small amount of chopped fresh fruit (typically apple and pear, though fruit types varied each day). As part of the study, we changed the food presentation, providing instead full pieces of fruit in addition to the seed based diet. Both chopped or whole fruit was provided in the same place, irrespective of food type. No changes were made to the normal seed mix.

To test the effects of this novel diet presentation, we measured the behaviour of the two macaws using an instantaneous focal sampling method. We also measured the amount of food that was eaten under both different conditions, by weighing the food in, and out again once observations were complete. Finally, we also measured the amount of time taken to prepare both the chopped and the whole diets. The research project took place over a three-month period between November 2017 and January 2018.

Behaviours:

To best study the macaws, we set up ethograms, which documented all the behaviours that were likely to occur during the study. The parrot behaviours were further separated into states (behaviours of long duration, such as resting), and events (behaviours that happen very quickly, such as calls). The ethogram used was sufficiently generic that it could be applied to other parrot species for extension of the project. The ethograms for the study may be found below:

Table 1: Ethogram of state and event behaviours.

| Behaviour/State | Explanation |

| Allo-preening | One macaw is seen preening the feathers of the other macaw using beak |

| Auto-preening | One macaw is seen preening own feathers using beak |

| Climb | Movement of the feet and/or beak 3 times to result in a vertical change of location |

| Feed | Macaw is seen swallowing a type of food (apply to both fruit and seed) |

| Fly | Movement of wings resulting in elevation off the ground and moving location |

| Forage | Digging in enclosure floor using beak |

| Locomotion | Movement of the feet 3 times to result in a horizontal change of location |

| Out of Sight | Inability to see where the bird is situated; behaviour is unknown |

| Resting | A lack of movement, can be resting on perch, bars, or other features of the enclosure |

| Event | |

| Allo-feeding | Food from the beak of one macaw is seen passing to the beak of the other macaw who then swallows the food |

| Allo-picking | Macaw is seen plucking the feathers of another macaw followed by visual falling of the feather and potential vocalisation of the victim |

| Auto-picking | Macaw is seen plucking own feathers followed by visual falling of the feather |

| Beak Manipulation | Flesh from the food is removed from the skin using the beak |

| Inter-aggression | Aggressive behaviour observed in the macaw acting upon jenday conures |

| Intra-aggression | Aggressive behaviour observed in the macaw acting upon the other macaw |

| Podo-manipulation | Crushing or ripping of the fruit using the foot |

| Chewing | Repeated chewing a minimum of 3 times on enclosure features - bars, perch |

| Vocalisation | Significantly loud noise from the macaw in a distinctive squawk |

Findings:

Chopped food is a standardised method of presenting diets and is used throughout many animal collections across the parrot keeping community. Surprisingly, however, we did not find behavioural benefits to support the use of a chopped diet.

Changes in activity:

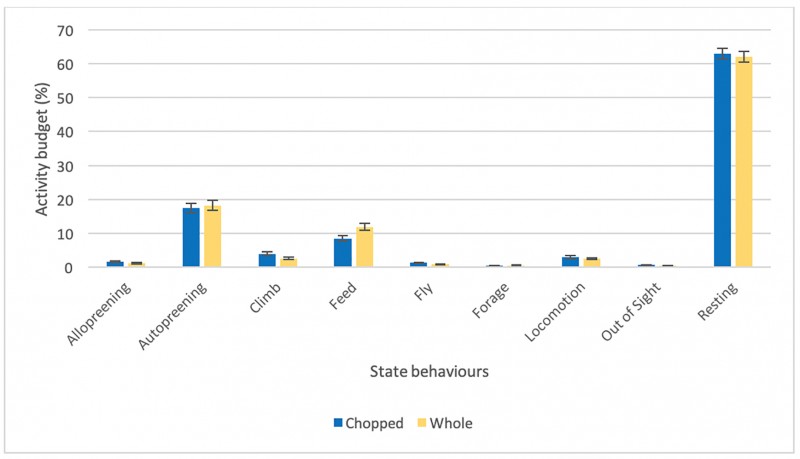

When fed their novel, whole food diets, there were surprisingly few changes to the normal activity budget of the two macaws. The amount of time engaged in resting behaviour was almost exactly the same for both chopped and whole conditions. A small, and non-significant increase was seen in the amount of time the parrots spent preening their feathers for whole food – this could be related to the messiness of the large food items. Perhaps the greatest change in behaviour was seen for feeding; on average both parrots spent considerably longer engaged in feeding behaviours when whole food items were provided.

Time taken for diet preparation:

On average, the preparation of the chopped food diet took 1 minute and 55 seconds of keeper time. By contrast, the whole food diet took only 58 seconds on average. While this saving of 57 seconds per meal may seem petty and insignificant, this could quickly mount up for collections that house multiple birds of multiple species.

Amount of food eaten:

Upon weighing food back in after observations, a small but significant increase was seen in the amount of food eaten when whole foods were provided. On average, 26.7 grams of food were eaten for the chopped food, and 34.0 grams for whole feeds. One of the concerns about the project was that the birds would be ill-equipped to feed on whole food items, not knowing how to manipulate and chew the items. This increase in food eaten seems to suggest the opposite, as the macaws appeared to be feeding more enthusiastically on the fruit. However, several confounding factors should be considered here. It is likely that more of the peels of the whole foods may have been discarded to the floor for the whole foods, and the feeding of the Jenday conures must also be considered.

Allo-feeding:

Allo-feeding is an unusual behaviour, in which one bird (normally the male) regurgitates food or presents food in its beak to another bird. Allo-feeding appears to be related to bond reinforcement and bond development between paired birds, however more research is required in this area.

As a short scale project which took place largely during the winter months, relatively few incidences of allo-feeding took place. However, it is very interesting to note that allo-feeding occurred on a greater number of occasions when the whole food was provided. In order to determine whether this was fluke, we have also made early observations of several other parrot species, namely the chattering lorry (Lorius garrulus) and slender billed corella (Cacatua tenuirostris) which are also housed at Beale Wildlife Park. We found similar, greater occurrencesof allo-feeding when given whole food items, though more research is needed here.

Bar biting:

Bar biting was a behaviour seen most often in the female macaw, and this behaviour might be seen as an abnormal repetitive behaviour. When provided with whole foods, we observed a significant decrease in the prevalence of this behaviour. It may be that the birds were spending longer manipulating their foods, and therefore had less time to spend engaged in bar biting. On the other hand, the addition of whole foods might have satisfied the birds’ need to manipulate objects with their beaks. Further studies may be required here!

Green-winged macaw bar-biting

Discussion:

As a study of just two birds, this project is just an initial investigation into potential benefits of a chopped or whole food provision format. Our early results suggest that whole foods may actually have behavioural and physiological benefits for parrots that could help to fill their activity budget. It’s likely that other parrot species may indeed react different to whole food formats – which is why we suggest that a rapid change to whole fruit items only is unlikely to be suitable. However, whole fruit could be used as part of a normal enrichment programme, and provided for birds perhaps on a weekly basis.

Our study has several future directions that require investigation. In addition to 1) investigating whole food provision for a wide range of parrot species, we would like to 2) investigate the effect of individual fruit items. Currently, we have investigated only the suitability of relatively soft fruit items. How would macaws react to much tougher food items, such as pineapples or melons?

As members of the Parrot Society UK, you are likely to have contact with a range of parrots that could benefit from whole food items. Our research project would benefit from a greater scope across as many frugivorous species as possible. Many parrot species, despite being well represented in captivity, have actually been poorly studied. Small scale research projects can therefore help to promote better understanding of husbandry needs for many psittacines. If you are interested in our research, the authors of this article may be contacted at James.Brereton@sparsholt.ac.uk, and james.charlotte@hotmail.co.uk.

Further reading:

Our initial research into the topic of whole food diets covered a mammal, the ring-tailed coati. The paper is free to download online on the Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research, from the January 2018 issue:

Rozek, J. C., Danner, L. M., Stucky, P. A., & Millam, J. R. (2010). Over-sized pellets naturalize foraging time of captive Orange-winged Amazon parrots (Amazona amazonica). Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 125(1-2), 80-87.

Shora, J. A., Myhill, M. G. N., & Brereton, J. E. (2018). Should Zoo Foods be Coati Chopped? Journal of Zoo & Aquarium Research, 6(1), 18-24.

Smith, A., Lindburg, D. G., & Vehrencamp, S. (1989). Effect of food preparation on feeding behavior of lion‐tailed macaques. Zoo Biology, 8(1), 57-65.

Blue & gold macaw enjoying a shower at Beale Wildlife Park (AKJ)