Bacterial Cultures in Parrot Disease Diagnosis

Alan K Jones October 2020. This article was originally published in the late John Stoodley's book 'Genus Amazona' in 1990, and was recently reproduced as part of a series of articles in the Parrot Society's monthly magazine. It was written by one of the pioneers of avian veterinary medicine, Greg J Harrison DVM, and has a lot of relevance still today. The chapter on parrot diseases in my book 'Keeping Parrots - Understanding their Care and Breeding' - mentions that illness caused by bacteria accounts for less than 25% of cases in sick parrots. Therefore antibiotics and bacterial testing are unnecessary and ineffective a lot of the time. However, smears and cultures are easy tests to carry out, and are often both over-used and over-relied upon by both aviculturists and veterinarians. Here are Greg's wise words, remembering it was written at the end of the 1980s -

"As aviculturists become more concerned about protecting their investment in birds, they are starting to get seriously involved in the medical management of their aviaries. Small animal veterinarians are also developing the avian side of their practice as they become aware of an increased need for their professional services. On the surface, this appears to be a very positive step. However, at this stage of our development of avian medicine, the results I see as a consulting avian practitioner are not always so positive. The energy and enthusiasm may be misdirected.

For one thing, many of the initial interactions between the aviculturist and the Veterinarian are for the purpose of ‘putting out a disease fire’. Few aviculturists realise there is usually a reason they have these ‘fires’ and there is often a prevention for them. During a disease outbreak, the attention is placed on saving the flock, and the latest drugs to hit the market are frantically sought to aid in this endeavour. There is little interest at this point in how this might have been prevented. When the outbreak is under control, the experience is often so expensive and devastating, the aviculturist would just as soon never see a veterinarian again. Everyone loses – most of all the birds.

Another problem I see is that well-meaning aviculturists decide to screen their birds for diseases. This usually means setting up a ‘lab’ where they use basic Gram’s stains and simple bacteriology test kits. The inherent dangers in this will be discussed below (Prevention of Bacterial Diseases). Novice avian practitioners are often guilty of similar assessments. Similarly, the veterinarian new to avian therapy has a tendency to search the literature for a drug dose chart, believing that birds are either ‘sick’ or ‘well’ and that administration of the latest drug will make the difference. Avian diseases are not so black or white. Numerous factors are involved in successful reproduction, and disease prevention is the most economically sound base on which to build a successful aviculture programme.

This blue & gold macaw is clearly very sick - but why? Does it have a bacterial infection?

Prevention of Bacterial Diseases

Aerobic bacteria (those requiring oxygen) are the easiest organisms to detect and grow on ‘quickie’ test kits. Bacteria will almost always be found, if that is what one is looking for. However, the mere presence of bacteria does not indicate a bacterial disease. A major error I see is the immediate administration of antibiotics in a ‘shotgun’ approach at the first sign of bacteria without regard for the total bird and its environment.

Common Misinterpretation of Laboratory Data

Suppose a faecal culture has been taken as part of a flock survey. The aviculturist has experienced no disease problems; no new birds have been brought into the flock in the last year; and no birds receive what is considered to be an excellent diet. The physical exam reveals no visible problems and a Gram’s stain of the faeces is considered normal. Yet, the culture might reveal light growth of gram-negative rods.

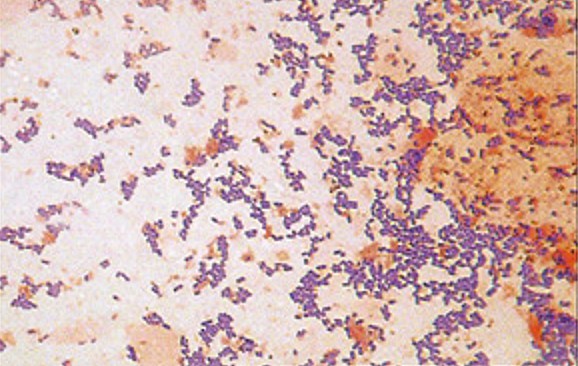

Faecal smear stained and examined under a microscope. Orangey-red patches are cellular debris. The multiple rods stained purple with Gram stain are bacteria, staining 'Gram-positive' These make up the bulk of normal parrot gut bacteria (Photo: Harrison's Bird Foods)

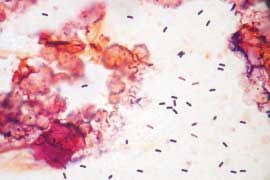

Another stained faecal smear, again with large coloured blobs of cellular debris, plus purple rods of Gram-positive bacteria, and similar-sized pink rods of Gram-negative bacteria (Photo: Harrison's Bird Foods)

This is a typical case where antibiotics are often indiscriminately used without regard for the overall picture. There could be many explanations for these cultural results in a clinically healthy animal:

- Bacteria from food may have been just ‘passing through’ the gut at the time of faeces collection.

- Bacteria may be passed as a result of some stressor, such as a cold spell.

- The sample may have been contaminated during collection, packaging or shipment.

- The laboratory may not have adequate expertise in dealing with avian microorganisms.

- The laboratory may have made a reporting error.

Bacteriology is a complex procedure that cannot be adequately performed with a simple test. Proper culturing techniques are beyond the capabilities of most veterinary clinics (and aviculturists’ ‘labs’). Although the growing of some bacteria is easy, its relationship to the condition of the patient in question may not be clear. If smearing faeces on a blood agar plate and putting it into an incubator was the answer to diagnosing avian diseases, we would have no problems left to treat. Although many laboratories adequately perform mammalian or human microbiology, there are not yet quality standards or criteria for avian work (no longer true in 2020 - AKJ) and, unfortunately, much of the information derived from some cultures is of no value to the practitioner. Many novice veterinarians take the lab reports as ‘gospel’ and treat according to the test results, rather than treating the bird. The physical examination, history, and results of other diagnostic tests must be interpreted in conjunction with a culture.

Bacterial colonies of Escherichia coli (E. coli) growing on an agar plate

In one instance, samples from the same bird were sent simultaneously to four different laboratories. The results indicated four different bacteria (one from each lab) and recommendations for the use of three different antibiotics. Blind following of these recommendations could lead to dangerous overuse of antibiotics.

In this author’s practice, a bacteriology culture is not one of the first diagnostic tests ordered, although it may be appropriate in some cases of a sick bird from a well-managed flock, a valuable bird, or a bird with certain clinical signs. The length of time required to get results (24-48 hours) also inhibits the selection of this diagnostic test in the face of a sick single pet parrot. I usually prefer to spend the client’s funds on blood work-ups, endoscopy or radiographs so the entire bird can be evaluated; then if bacteriology is indicated, the results can be coordinated with these other parameters.

Isolation of Bacteria

Growth of E. coli, Proteus, Klebsiella or Enterobacter is generally believed to indicate other underlying problems. If the culture shows truly pathogenic bacteria, such as Mycobacterium avium (T.B.), Yersinia, Pasterella or Salmonella sp., then one must find where it came from. These bacteria are reported to be the cause of some reproductive failures, yet they almost never show up on culture reports from the laboratory. More attention must be paid to how these organisms can be uncovered by the diagnostic community in live birds Then one must ask the questions, ‘Is it worth treating?’ and, ‘Should the bird be kept as a breeder?’ Many of these serious organisms are resistant to antibiotics and only partial ‘cures’ with long-term, intermittent shedding of the organisms are common. With M avium, the potential risk to humans from exposure is considered too great by most authorities to recommend treatment of an affected bird, because the disease is often fatal in man. However, it appears many birds may be harbouring anti-bodies against this organism; thus, the true clinical picture is not clear at this time. I would tend to suggest eliminating any birds from the flock that are shedding acid-fast organisms after identifying the type of organism present through use of an antibody test.

Little is known by most people dealing with parrots of the true meaning of finding gram-negative bacteria. There is also a lack of respect for the role of ‘good’ bacteria in the overall health of parrots. Because of this, many psittacines are treated unnecessarily; some are even being harmed by overuse of antibiotics, and the real underlying problem missed completely."

See also - As Sick as a Parrot