Wing Clipping

Wing Clipping in Pet Birds - an update 2023 ©

by Alan K Jones BVetMed MRCVS (Retired Avian Veterinarian & PSUK Scientific Advisor)

Free-living Lear's Macaws (Anodorhynchus leari) in Brazil 2016 (AKJ)

There are few things more glorious in nature than seeing a colourful parrot spreading its wings and flying through its natural habitat. Apart from the ground-dwelling Kakapo, these birds were made to fly, and it is an amazing sight. However, once we bring them into confinement as pets, curtailing this activity by clipping their wing feathers had become commonplace. However, the technique is contentious, and many veterinarians and parrot enthusiasts denounce it as being unnecessary and cruel, while many breeders and pet stores selling parrots to the pet market still wing-clip young parrots as a matter of routine. The original post on this page was based on a talk about this thorny subject that I presented to the Association of Avian Veterinarians at its annual conference back in 1996. Much of what I said then will demonstrate that it is a complex subject, and there is no black and white answer. There is no reason to call for a total ban on wing clipping, neither should every bird sold as a pet be clipped routinely . Equally, if and when birds are clipped, the technique will vary according to the species involved and the individual situation, but there are a number of ways of clipping birds’ wings that are positively wrong and should be discouraged. The Parrot Society UK is actively involved in welfare issues for captive birds, which will include the clipping of wings. I hope this article will help PS members to form an opinion on the subject. There is no doubt that as we better understand the psychological and welfare needs of captive parrots, the practice of wing clipping is likely to disappear. Since this original website posting in 2018, the text has been further revised, in light of changing opinion on the subject, and follows here:

Let me start by saying that when I first wrote on this subject back in 1996, the clipping of wings in pet parrots was a readily accepted, common, everyday procedure, but over the years it has become an increasingly uncommon practice, and in many quarters it is actively discouraged and even vehemently disapproved of. Historically, wing clipping was put forward as a way of ‘taming’ a young bird – because it couldn’t fly away from its carer, it was made more easy for the human to handle the bird. Such was its acceptance at the time that most young parrots sold from pet stores or by breeders were routinely clipped before handing over the bird to its new owner. Over the ensuing decades, we have come to understand more about the welfare needs of parrots, and that there are far better ways of taming a parrot by training and reward. The risk of escape by flying away is also better mitigated by harness training, or better vigilance over open doors and windows, and having parrot-proof locks on cages and aviaries!

Undoubtedly, the practice of wing clipping is dying out, but there are a few owners of pet parrots who hold out for having their birds clipped, only to find that most avian veterinarians will now refuse to do so. The professionals will quite rightly try to explain the reasons why, and offer alternative management and training techniques, but persistent clients will then end up turning to pet shop staff or amateur ‘experts’ to get the procedure done, often with disastrous results, and this is where the information that follows becomes important. If and when birds are clipped, the technique will vary according to the species involved and the individual situation, but there are so many methods of clipping, many of which are useless, or even damaging, that if the technique is to be used in pet captive birds, then it must be our duty to achieve some uniformity and to educate others as to the correct technique. This article will describe the various methods and will discuss their relative advantages and disadvantages.

Reasons for Wing Clipping

The feature that sets birds apart in the animal kingdom is the fact that they possess feathers. These give the power of flight in most species and provide the form and colour, which attract us to keeping birds. However, in the pet bird situation, where an avian species is a family member and is allowed freedom in the household, the power of free flight can be a positive disadvantage and even a hazard to the bird. Fully flighted birds will get into areas where owners may not want them; they may damage ornaments and decorations; they may reach materials that can be chewed, such as door and window frames; they may fly into fires or cooking pans; and in the summer they may escape through open doors and windows.

We also encounter mate aggression in paired birds, where one enthusiastic partner (usually the cock bird) in the breeding season can continually chase its mate, who may not yet be in breeding condition. This will result in fatigue and loss of condition in the chased bird: very often feathers are damaged, the bird will not be allowed to feed, or will be physically attacked. Clipping the wing of the aggressive partner will reduce such harassment and will allow the mate to recover while she comes into breeding condition. In all other circumstances, paired birds living in aviaries should be allowed free flight.

As mentioned in the introduction, there are many alternatives advised these days to manage the above problems, using training and husbandry techniques. However, there may still be some who persist in pursuing the idea of clipping.

It is in theory a simple operation to cut some feathers so that the bird cannot fly, but the correct method requires some knowledge of feather anatomy and the different flying abilities of various species. There is no one technique that can be applied to all birds. Waterfowl and other birds kept in open collections are often pinioned as young birds. This is a surgical procedure which permanently removes the metacarpal section of the wing and thereby the flight feathers, so rendering the bird flightless for life. This will not be covered in this article: neither will the amputations of all or part of the wings for medical reasons.

Wing and Feather anatomy

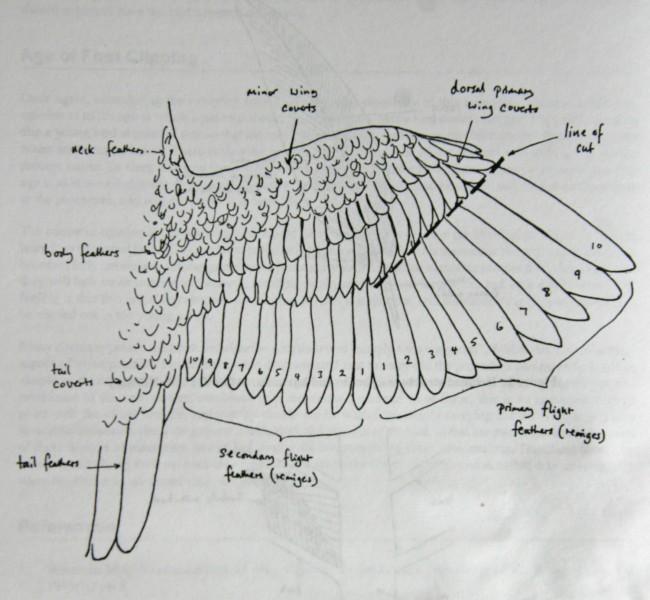

The wing of the bird is the pectoral limb, whose skeletal framework is the humerus, radius/ulna, carpals, metacarpals and phalanges. This supports a soft tissue web of ligaments, tendons, blood vessels and skin. These webs are termed patagia. From this tissue grow the feathers, which have a cylindrical supporting shaft, or quill, composed of keratin and growing from each side of the shaft is an interlocking system of barbs and barbules, which are also constructed of keratin. These impart the colour of the plumage; provide an insulating layer by trapping air between the feathers; offer a waterproofing effect by virtue of their oily coating; and by their interlocking nature, provide an aerofoil action to allow flight. From the trailing edge of the wing arise the long flight feathers, which are those relevant to wing clipping. They naturally divide into primary and secondary flights (see diagram 1). The remaining feathers of the wings are smaller contour feathers, which where they overlap the flight feathers are termed coverts.

The technique

The aim of the procedure is to allow the bird controlled downward flight, with no possibility of lift. The bird should not fall heavily to the ground: this will often result in injury to legs or sternum. The method chosen must achieve this objective while at the same time satisfying the aesthetic requirements of the owner. It is important to discuss first with the owner the various options and to indicate to them that wing clipping provides only temporary control of flight. Many owners do not realise that once the bird moults and loses the cut feathers and grows new ones, it will fly again. They therefore need to be prepared to return to have the procedure repeated on a regular basis: the frequency will depend on the species and the stage of the moult at the time of clipping – see later.

The bird will need to be restrained comfortably, preferably with the aid of a competent assistant or technician. A towel should be used for the larger parrots, while a cockatiel or smaller bird may be held in the bare hand. It is never advisable to allow the bird owner to hold their pet for this procedure: most are unable adequately to restrain the bird safely; many are tense and therefore in danger of holding the bird too tightly; plus the fact that the bird will then associate the experience with its owner and may lose its trust in the owner.

The wing to be clipped should be gently but firmly extended, holding it over the radius/ulna. The selected feathers may then be cut. Blunt-ended scissors may be appropriate in the smaller species, but these will slide off the quill of larger birds, making accurate cutting impossible. Open-ended nail clippers should be used in most birds, with a final tidy-up of the barbules with scissors where necessary.

I have seen many suggestions by various bird keepers to which feathers should be cut and how. Some operatives have suggested cutting alternate flight feathers to retain some appearance of normality. This will not work – the bird will still fly. See the discussion of the moulting process later. An alternative suggestion is to cut along the length of the shaft, removing the barbs, but retaining the quill (fig 2). My response to this technique is “why”? This simply leaves exposed shafts, which will inevitably irritate the bird and lead to feather mutilation.

Primary feathers on an African grey parrot clipped along the length of the quill (AKJ)

The preferred method is to cut primary feathers along the line of the eternal wing coverts (figs 1,3&4). This reference point is significant: to cut at a level lower than this line will allow the bird still to fly.

Amazon parrot with full wing (left); and clipped primaries along the line of covert feathers (right) (AKJ)

Whilst the feather cut may be tidied up to just under the covert line, it is important not to take the cut too high. Note that the external wing coverts extend further that the internal feathers. If these are used as a reference, the trim will be too high. This can result in two problems: the first is that new growing feathers, still encased in their protective sheaths (“blood feathers”) may be cut, with resulting haemorrhage. The shorter cut will also mean that the quills left may create a problem at the next moult, similar to the situation found when recently trapped birds taken for importation, are savagely and carelessly hacked by the native trappers to prevent them flying. These over-short feathers become a source of irritation to the bird and in many cases will lead to feather plucking. It is my opinion also that the natural moulting process depends in part on the weight of the old feather pulling at the follicle and gradually working loose. If the feather stump is too short, then this weight stimulus is not present and the feathers are not lost at the proper Interval. I have seen birds damaged in this way, still carrying these short quills 18 months after being chopped. The ends of the feathers become frayed in time and again a source of irritation to the bird, leading to feather destructive behaviour.

Top - new blood feathers growing in at tip of heavily clipped wing. Below - severely damaged quills chewed by bird following excessive chop

The next – and most important – dilemma is how many feathers should be cut? The answer has to be variable, according to the species involved. Light-bodied, long winged strong-flying birds like cockatiels will require more feathers to be removed than will a stocky, short-winged species such as an Amazon parrot. Each patient has to be treated individually and the required effect discussed with the owner. An obese pet Amazon parrot may require only 4 or 5 feathers removed. My preference is to retain the outer primary feathers (9 and 10) for cosmetic effect provided when the wings are in their resting position crossed over the body. This is controversial, with many veterinarians suggesting that this leaves these outer feathers vulnerable to injury. When dealing with the strong flyers, it is essential to take 7-10 feathers, including the outer flights 9 and 10.

After the clip is performed, the bird should be tested to ensure that the desired effect is achieved. If not, more feathers may be cut, after consultation with the owners to confirm the required degree of flight control. There is also discussion among veterinarians as to whether one or both wings should be clipped. The general feeling and current practice is that both wings should be cut to avoid the ‘spiralling’ effect of clipping just one side.

Clipping the secondary flight feathers certainly will not prevent flight! Yet I have seen many birds clipped by pet-store workers or inexperienced veterinarians in this fashion (fig 5). Owners naturally become upset when their birds still fly around their heads, or worse still, escape! I have also encountered clips where all primaries and secondaries have been removed. This is excessive and unnecessary.

African grey parrot with secondary flight feathers clipped. This bird will still fly! (AKJ)

Frequency

As mentioned earlier, we have to consider the natural lifestyle of the bird: worn-out feathers are regularly replaced in the process known as moulting. In a few species, mostly waterfowl, this takes place in a short period, with most of the flight feathers lost in one go. This is known as an 'eclipse moult'

Wing of a duck showing new blood feather growth of all flight feathers following eclipse moult (AKJ)

This renders such birds temporarily flightless and therefore vulnerable, but in the majority of birds the replacement process is sequential. It therefore follows that wing clipping is a temporary process, with the cut feathers gradually being replaced by new growth. This seems often not to be appreciated by pet bird owners, some of whom seem to consider that clipping is a once in a lifetime procedure, so it is important to explain this fact to the client. The interval between rendering a bird flightless and the return of aerobatic ability will depend on the stage of the moult at which the clip was performed. If the patient has recently moulted at this time, then it will be 6-9 months before new growth takes place. Conversely, if the bird is due to moult when clipped, then new feather growth will occur within a few weeks. It will take only 2 or 3 replacement feathers in strong flying species for flight to be possible. The owners must be advised of this and should expect to have the bird trimmed again soon.

Age at first clipping

Once again, considering the everyday nature and apparent simplicity of this procedure, there is conflicting opinion as to the age which a pet bird should first be clipped. As I mentioned at the outset, many bird dealers and pet shops would routinely clip a young bird at point of sale so that the new owners have no problems with their new pet flying around the house and causing havoc. There is also the opinion that such restraint of the new pet will make the taming process easier and that clipping a young bird at this age is akin to nail clipping or grooming a puppy, with the expectation that the animal will become accustomed to the procedure and will not resent it in later life.

These thoughts are fortunately losing ground to the converse opinion that a young bird should first be allowed to develop the physical ability to fly and to learn how to control that ability properly, before it is taken away from it. This means that the pectoral musculature becomes fully developed. African Grey parrots particularly seem to require a learning process for flying otherwise they lack co-ordination and control, resulting in physical injury to themselves and their environment. My feeling is that this initial learning and developing process is important and therefore wing clipping should not be carried out in too young a bird.

I hope that I have demonstrated that to carry out the procedure completely is not as simple as it first appears. The technique will vary with the weight and species of the bird, the experience and preference of the veterinarian, combined with the owner’s wishes. If it is performed by a veterinarian, then the consultation is also an important contact point with the client and the opportunity should not be wasted by simply carrying out the wing clip. There should be a discussion about the general health, diet and housing of the bird, so that the owner can be made aware of these aspects of aviculture and of the service we can provide as avian veterinarians. The client should be encouraged to bring their pet back on a regular basis for health checks and discussion, rather than arriving only when the bird is in an advanced stage of illness.

I repeat that the foregoing is not in any way official Parrot Society UK policy towards wing clipping. It is purely my personal opinion, based on over forty years working in pet-bird veterinary practice and it is intended to put forward the advantages and disadvantages of what seems on the face of it to be a simple technique. There are very many bad wing clips performed by inexperienced operatives, or those who do not understand the mechanics of birds’ flight. These cases have brought the technique a bad name, and there is a general move away from the technique on welfare grounds.

I accept that the majority of birds are just built to fly and there is no greater sight than watching these magnificent creatures, soaring, hovering, swooping, gliding and flapping in their natural environment. However, if we accept the premise that we are going to keep such creatures in captivity (and that in itself is controversial to many people!), then we must also accept that this modification of their lifestyle brings with it many changes. If wing clipping can make that lifestyle safer and allow greater freedom for the pet bird, then my contention is – provided it is carried out properly and efficiently – that this technique still has a valid place in pet bird husbandry, in a small minority of cases.

© Alan K Jones BVetMed MRCVS July 2023